- Home

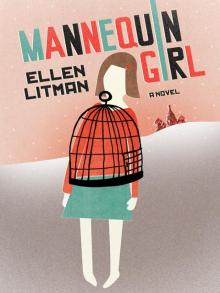

- Ellen Litman

Mannequin Girl

Mannequin Girl Read online

For Ian

CONTENTS

Part I: 1980

1

2

3

4

5

6

Part II: 1986

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Part III: 1988

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Acknowledgments

1

IN JULY SHE BECOMES AN ANOMALY, A GLITCH IN A plan, a malfunction in an otherwise perfect mechanism. There is no pain, no warning signs, and no heredity issues, contrary to what the doctors imply. Her mother says Kat’s diagnosis is a slap in the face and a curse and the blackest day of their lives. “You should’ve seen us,” she says. “We were black when we came from the doctors.” Her mother’s face is white, her hair short and dark. She resembles the champion figure skater Irina Rodnina, and everyone knows she is prone to verbal extravagance.

The day Kat will remember is hot and bright. The queues at the children’s policlinic, the smell of iodine, the hard cardboard cover of the novel she’s reading: The Wonderful Adventures of Nils. Her mother, too, is reading. They’ve come for Kat’s physical, which she needs for school.

She is starting first grade in September. All the school forms have been assembled and nearly all the shopping is done. For the Knopman–Roshdal household, this in itself is atypical. Kat’s parents are bohemians, fantastically disorganized. But in this instance they surpass themselves. The school is their milieu, their pride. They teach Russian and literature, and run a drama club, and whatever might be said of their slipshod ways at home, at school they are unrivaled, they are loved. As T. N. Zolotareva, who teaches grades one through three, puts it, they are the school’s last hope.

Naturally Kat has to ask what is wrong with the rest of the school, and T. N. gets flustered for a moment. The school, after all, is like any Soviet school—politically savvy, ideologically grounded, its teachers 60 percent Party members, two exemplary educators, one educator-methodologist. As for Kat’s parents, they are still too young to have any distinctions, and also they happen to be Jews.

Kat already has a bit of reputation at the school. She is known as a local wunderkind: she reads on the par with fifth-graders, spews quotes from memory, soaks up everything—epigrams, quips, staircase conversations, the merciless assessments her parents bestow on their associates and friends. She plays a page in her parents’ school productions; at holiday parties she and her father enact short comic sketches.

At home, her parents call her “our little bureaucrat,” which doesn’t upset her, not in the least. She’s organized, responsible. Somebody has to be, with parents like these. Though of course, she adores them. They are brilliant, daring, the kind of parents who’d risk anything for truth. The least she can do is remind them when they are out of milk, or when their apartment payment is due.

This summer they need few reminders. They spend money with abandon on pencils, pens, counting sticks, stacks of thin notebooks, extra sets of penmanship exercises. They travel by subway to Children’s World to buy Kat her first uniform, an itchy brown dress with two pinafores, one white and one black.

At home, each item is stashed in the three-door wardrobe in Kat’s room, and every afternoon she inspects her new riches: the dress with its snowy accents of lace, a satchel and a silky bag for shoes, new ribbons. She is growing out her hair. By the end of the summer it will be down to her shoulders. She’ll have braids on her first day of school. For now, she fixes it up in two sickly pretzels, and when no one is looking she puts on her new dress, too. She loves how it slims her into a whole new person, all grown up and tidy. The skirt flares slightly, and whenever she has the dress on, she wants to twirl, twirl, until the world spins around and gravity loosens its hold on her.

Later she takes the dress off, puts it back on its hanger, makes sure there’s not a speck of lint on it, not a wrinkle on the seat of the skirt. She is ready. She’s been ready since the start of summer—except for the physical, which her parents have been calling a stupid formality. This flippancy alone should have tipped her off. Formalities, she is to learn, have a way of wreaking havoc on your life.

THE QUEUES are enormous at the district policlinic. They have to see a battery of doctors—an oculist, a dermatologist, an ear-nose-and-throat specialist, a neurologist, and many more. They do what any sane person would: secure their spot in several queues (with the standby excuse of “I’ll just step away for a moment”), and every ten minutes Kat goes to check on their progress in each queue.

It doesn’t look good. The hallways are chock-full of sniveling babies; they spill and holler everywhere. Their mothers—crude shapes in flowery summer patterns—try in vain to keep hold of them. The mothers glower at Kat, and their looks promise nothing positive. They don’t care that she’s a child herself. You want your turn, they say, you wait like everybody else.

“I can’t do this,” Kat whimpers, returning to her mother, who has planted herself on a low red banquette by the blood lab. “I can’t deal with these people.”

“Then don’t,” Anechka says, and stretches slowly. She looks sleepy and gorgeous in her T-shirt and knee-length pants with cuffs and buttons, like the actress N. Varley from Kidnapping, Caucasian Style. A beauty, a Komsomol member, an athlete! “Don’t fuss, don’t fret, and people will flock toward you.”

“I don’t want them to flock,” Kat says.

“It’s an expression, baby. They’re just cattle, you have to understand. You can’t waste your intellect on cattle.”

“At least you could have helped,” says Kat. But she knows it’s useless: Anechka doesn’t help. She doesn’t quarrel with the masses, doesn’t demean herself in daily skirmishes, doesn’t squabble over a vacant seat on the bus or lose face over some bread or cabbage. If she needs bread and cabbage, she’ll send Kat’s father to the shops.

“Baby, calm down. You’re fraying your nerves.”

Kat’s nerves are already in a shambles.

Her eyes, on the other hand, turn out to be perfect. In the oculist’s office, she is told to shield one eye with a small plastic paddle. There’s a poster filled with round shapes and another one with the alphabet. Kat says she prefers the alphabet, but the oculist woman says she might mistake a letter. “I don’t make mistakes,” Kat says.

“You’re a disgrace,” Anechka grumbles, as they wait outside the orthopedics office, their last appointment.

“Because I can read?” Kat says.

“Don’t play daft like you don’t understand me.” Reading isn’t the problem. Reading is great. The problem is behaving, being a decent girl, not arguing with adults, not talking back. “You’ll be at our school next year. If we can’t discipline our own daughter—”

“When did you ever need to discipline me?”

“Plenty of times.”

“Like when?”

“Don’t be a nudnik,” Anechka says, which is what she says when she runs out of arguments—which, truth be told, doesn’t happen very often. The problem is, she has no patience. One moment she’s all smiles, and the next, seemingly with no provocation, she’s spinning herself into one of her snits. “A rein’s got under her tail” is how Kat’s father sometimes puts it, though never within Anechka’s earshot.

THE ORTHOPEDICS doctor, a big flabby blonde, has a voice like the folk singer L. Zykina, unwavering and droning. Any moment now she’ll burst into a song: “Orenburg Downy Shawl.” She tells Kat to undress; she tells her to bend forward. “Lower,” she says. With her blunt stubby finger, she pokes her below her right shoulder blade.

“There!” Another poke, now in the lower back, on the left.

“It’s like you parents don’t have eyes,” she says. “Don’t you look at your daughter? In the shower? When she undresses for bed?”

“Of course we look at her.”

The doctor tells Kat to get dressed.

“First they neglect their children, and then it’s up to us—and the government—to bear the consequences.”

“What consequences?” Anechka says, quietly, gravely, as if making a threat. “What on earth are you ranting about?”

“Me ranting?” The doctor goes all aflutter. “You’ve got yourself a girl with an ailment. Third-degree scoliosis. That, mamasha, is a sign of neglect. You should be deprived of your parental rights. You’ve crippled your daughter.”

When they come out of the office, Anechka’s eyes are pitching lightning bolts. She crumples the referral papers, shoving them in clumps into her bag. “Swine,” she is muttering to herself rather than Kat. “Insolent piece of garbage. Fat, uncultured, ballooning on bribes.”

“What about school?”

“I don’t know,” snaps Anechka.

In the days to come, Kat will rehash it many times—“crippled, ailment, scoliosis”—and it will dawn on her eventually, the full extent of her misfortune. She’ll learn that scoliosis is a curvature of the spine; that in the best-case scenario its progress can be halted; that it can only be diminished with surgery, but even then the damage can never be fully undone.

Her father meets them by the door of their apartment—barefoot, warm and rumpled, bleary from an afternoon nap. He squints nearsightedly and clears his glasses, a look of surprise on his face. Life to Misha is a series of pleasant surprises. “Button!” he says, which is his pet name for her. “How’s my Button?”

If only he’d gone with her that day. It is a whim, a superstition; scientifically it doesn’t make sense, but Kat will never shake the conviction that her whole life might have turned out differently had she gone to the doctor with Misha.

IT’S BEEN a long, plodding summer. The asphalt streets are hot and cracked; the air quivers like the meat jelly Kat’s grandmother makes for holidays. The hot water has been turned off for its annual summer repairs. The Department of Residential Affairs has posted notices: “No hot water!” Outside, men in hard hats have begun drilling a trench. Moscow in the summer is no place for children. Children need nature: dachas, summer camps, the whispering of pine needles, the gurgling of a river or a lake. Or else they need a good Black Sea resort, with sand and a tan and turquoise waves and shish kebab in cafeterias—something Kat’s parents can never afford.

Anechka and Misha finished teaching back in May, but they still dart to school every day, first to supervise the summer practicum for the eighth-graders, and later, as far as Kat can tell, for no ostensible reason. They won’t take her with them. “Dust, Button!” Misha explains. Too much dust in there. Repairs, and so on. Meanwhile, the weather is marvelous.

“Marvelous, sure,” Kat grumbles. She waits for them at the playground, which isn’t even a playground but an empty, unpaved space with a couple of benches along the perimeter and a sandbox that smells so bad no one will touch it. Boys use the playground for soccer, while girls prefer the smooth, bouncy surfaces of sidewalks for hopscotch, jump rope, and elastics. Every game this year seems to involve classes, grades, advancing to the next level. Their world is normal, orderly, like a sheet of ruled paper, like hopscotch squares. They live in apartment blocks with identical floor plans.

The girls are the first to leave. Then the boys. For a week in late May Kat gets herself adopted by a group of older kids who drift in from neighboring streets. They play “The Sea is Roaring” and “I Know Five Names.” She is the youngest and the best at word games. “I know five titles of novels.” A bounce of the ball for every name. “One: War and Peace. Two: Vanity Fair. Three: Don Quixote.” Of course, she hasn’t read these books. Not yet. They are waiting for her, crammed into shelves, piled on the floor by her parents’ sofa, on the desk, in the corners. Still, her new friends are impressed. But after a week, they too disappear.

Kat stalks the playground alone save for a group of neighborhood grandmothers, who scrutinize her every step and question aloud what her parents are up to. It is the summer of the Moscow Olympic Games, and directives have been issued to remove from the city all children between the ages of eight and fifteen, lest they be exposed to foreign germs or capitalist provocations.

In the past, Kat’s parents took her to her grandfather’s dacha for the summer. At the end of May, the three of them would make their pilgrimage to Kratovo. A station-wagon taxi would be reserved in advance. The journey took two hours, and inevitably Kat got carsick after the meat-processing plant. The driver would be asked to pull over, and Anechka would get out some spare plastic bags. She’d call Kat her misfortune.

Their misfortunes didn’t end there.

At last, the taxi would pull into the shadowy yard of the dacha, and moments later, the craggy figure of Alexander Roshdal would stagger heavily onto the wooded path that led up to the two-story house at the back of the property, the house he occupied year-round with his second wife.

“Anya?” he’d say, as if his daughter’s arrival hadn’t been expected for weeks, but was instead a complete surprise.

For a minute, he and Anechka would study each other, their eyes meeting and making a pact—a pact, everyone knew, that Anechka would break by the end of the afternoon—and then, his knuckles whitening over the handle of his cane, he’d give her a one-armed hug.

ANYA, ANECHKA, Anna Alexandrovna Roshdal. Even after she married she didn’t give up her last name, making their family a hybrid, a two-headed dragon. Her father, Alexander Roshdal, had been a translator. Once upon a time he’d corresponded with the writer V. A. Kaverin, and had known others from the famed Serapion Brothers group. His wife, Anechka’s mother, wrote poetry—exquisite, mystical, and, according to her husband, utterly unpublishable in their days of fast tempos and five-year plans. He was a cautious man, he’d seen what had happened to the Serapion Brothers, and to others like them.

His wife was a beauty—a frail, fiery woman with a pale smile, feverish cheeks, hair like a dandelion about to be blown away. She died of a heart condition when Anechka was fifteen, leaving father and daughter alone and reeling, their grief so acute they knew not what to do with themselves.

They pulled through, of course—people recovered from worse blows than theirs—and scrambled out from under the wreckage. They lived idyllically in the one room of their communal apartment that was assigned to them, looking after each other, studying, translating, reading aloud in the evenings, cooking simple suppers of sausage and buckwheat kasha. Neither could do much in the kitchen. Foolish, impractical, they were a solace to each other, and it didn’t matter that their good silver disappeared gradually, their clothes needed darning, the floor hadn’t been waxed in years, the dust on the dresser was two fingers thick. But maybe it did matter. Because one day, Alexander Roshdal brought home Valentina, a woman of no literary inclinations.

Now there were three of them sharing the room, the new couple sleeping on the little sofa in the corner, where Anechka’s parents had once slept, and Anechka on her folding bed behind a thin partition. She was painstakingly polite to Valentina. She expressed her dislike in a language so circuitous, so elevated, that it was bound to go over Valentina’s head. Who was Valentina? A glorified washerwoman. The ancient chandelier was polished with tooth powder, the parquet floor now sparkled, and dinner became a regular three-course affair, with soup to begin and sweet compote at the end. Wasn’t Valentina fantastic? Wasn’t she talented?

Anechka’s compliments were duplicitous, laced with puns and contempt. If Alexander Roshdal saw through his daughter’s antics, he said nothing. And what could he say? He was the guilty party. He’d sprung his new lover on Anechka like a sudden snow on her head. The girl had been completely unprepared. He’d been caught by surprise him

self.

Now, thirteen years later, relations remain strained. A mother, a teacher, thirty years of age, Anechka Roshdal reverts to her teenage self the moment she steps onto the grounds of the Kratovo dacha. The food is too salty or else too bland, the house is too damp, and all the fresh air in the world can’t make up for the fact that she still has to share her father. Every day after breakfast she tries to commandeer his attention, taking him away from Valentina, inventing an errand for just the two of them—the department store in Udelnaya, the big outdoor market in Malakhovka. Misha and Kat are left to nap in hammocks while Valentina, always light on her feet, hums and spins, chops and sautés, weeds the garden, cans fruit for the winter, scuttles back and forth with her wicker shopping bag. All of it done gamely, with a smile and a wink, a treat for Kat, a joke for Misha.

Kat secretly likes Valentina, her perky face, flaxen perm, carrot lipstick. She even tried to defend her to Anechka once, which didn’t go down very well. Whatever Valentina had done in the past, surely she’d earned Anechka’s forgiveness since then?

“She made me an orphan,” said Anechka, and that, as far as she was concerned, was the end of that conversation. Kat never dared broach the subject again.

IT MUST have been that orphaned feeling that brought Anechka and Misha together. He too had lost a parent. His father, an officer, died in a botched surgery when Misha was three. His mother, Zoya Moiseevna, never remarried. She worked as a secretary at the Institute of Steel and Alloys and hoped her son would wind up a student there. Instead, her gentle Misha, in a rare display of bullheadedness, applied to the Lenin Pedagogical Institute. “Have you gone mad?” said Zoya Moiseevna. “You’ll crash and burn and end up in the army for the next two years.” When that didn’t work, she tried another tack: “Teaching is for girls, not for a boy.” She was desperate; they had no connections at the Pedagogical Institute. He applied and got in anyway, got in based on his own sheer brilliance, and fell in love with Anechka Roshdal before the winter exams—the two events Zoya Moiseevna later conflated in her memory, and never forgave either of them.

Mannequin Girl

Mannequin Girl